Europe’s solar goals caught up in high prices—and China

Latest News

The European Union wants to ally with the sun to boost energy security and meet climate goals but soaring prices for essential raw materials could thwart those plans.

Keen to cut its dependency on Russian fossil fuel imports, the European Commission, the EU’s executive arm, presented in May a strategy to double the 27-member bloc’s solar generation capacity by 2025 and almost quadruple it by 2030 to reach 600 gigawatts. It described solar energy as “the kingpin” of these efforts.

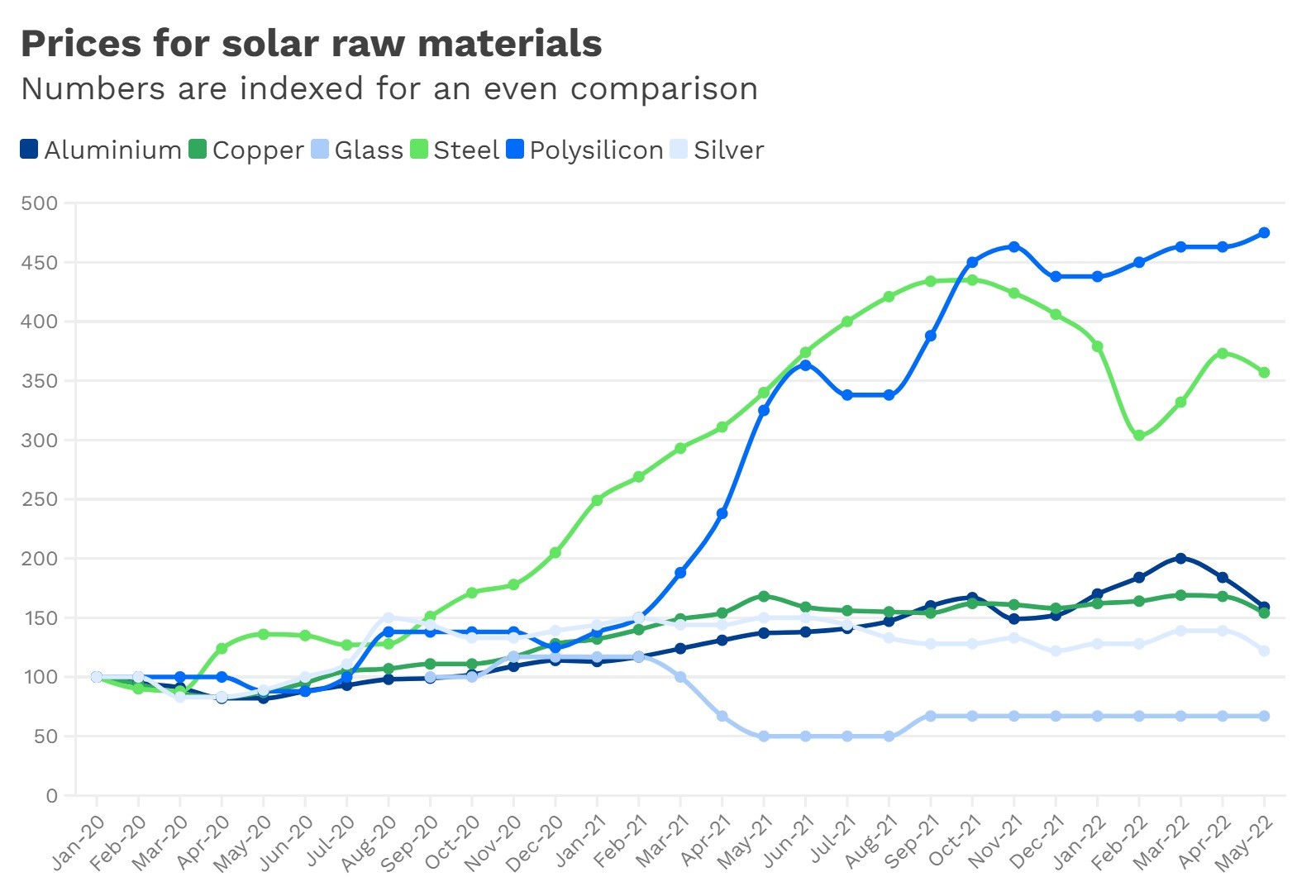

Polysilicon, the main raw material for producing solar cells that mostly comes from China, tripled in price over the last year and a half, according to an analysis from consultancy Wood Mackenzie. The prices for other raw materials needed in solar panels, such as steel or aluminum, have begun decreasing slightly in the last month, but they are still considerably above their 2019 levels.

Source: Wood Mackenzie • Prices do not show dollar values but are indexed from January 2020 with the starting unit 100

The increase in raw material prices is having a ripple effect on other parts of the supply chain like installations, which risks delaying projects, said Theo Theodorou, Wood Mackenzie senior research analyst.

“This is something Europe needs to have in mind,” said Theodorou. “How to navigate this high-cost environment—and it won’t be plain sailing.”

Polysilicon makes up about 4% of the weight of a solar module (the building block of solar panels), but it accounts for about a quarter of the raw materials’ embedded costs, he said. The jump in polysilicon prices also pushed solar module prices up by more than 20%.

Jochen Hauff, director of corporate strategy, energy policy and sustainability at BayWa r.e., a global renewable energy developer, service provider and distributor, said higher electricity prices—a separate but related challenge the EU is facing—have allowed his company to mitigate some of these higher costs by charging corporate customers more through power purchase agreements. PPAs are contracts in which a business agrees to purchase electricity directly from a renewable energy generator.

“So far, the price increases that we need to pass on to our customers [are] well within their willingness to pay,” said Hauff, who is also vice president of the board of directors at SolarPower Europe, the solar industry’s lobby group in Brussels. If prices go unchecked for a longer time, it could slow the industry’s growth, he added.

Raw material prices have spiked before, but “now we also have a never-seen-before demand of renewables,” Hauff said.

The EU’s lack of a solar manufacturing chain—a scenario also plaguing the United States—makes this global race for solar panels even more challenging.

Here’s a breakdown of a how a solar panel is made: Polysilicon is melted and then shaped to form ingots, which are cut into wafers and processed to create solar cells. Several dozen solar cells put together form a solar module. One or several modules comprise a solar panel.

The EU has a small and fractured manufacturing capacity across this chain. It can produce 23.2 gigawatts of polysilicon per year, but it has only 1.7 GW capacity to make ingots and wafers, 0.8 GW capacity to make solar cells and 8.1 GW capacity for modules, according to SolarPower Europe.

This means it must export almost all the polysilicon it produces to China, the manufacturing powerhouse, which then processes the polysilicon and provides the EU with 75% to 80% of the modules it needs.

Overall, China’s share in all the key manufacturing stages of solar panels exceeds 80% and is set to rise to more than 95% in the coming years for key elements such as polysilicon. That’s based on current manufacturing capacity under construction, according to a July 7 report from the International Energy Agency. (See our bonus Data Dive below for more.)

This additional polysilicon production capacity, set to come online in 2023, is expected to ease the current upswing in prices.

That’s good for combatting climate change, but it underscores the world’s dependence on China for clean energy materials. Experts worry such dependence is becoming a greater risk as use of clean energy grows—like Europe’s dependence on Russian gas today.

For its part, the United States has fought to stem this tide by placing tariffs on Chinese-made solar materials, but that hasn’t prompted a large domestic manufacturing base.

Setting up a new supply chain is always costly early on, which will make it challenging for the EU to compete with China in module prices, said Theodorou. “But they need to do it.”

Innovation to improve the efficiency of solar cells could help Europe lessen its supply chain challenges, said Christophe Lits, market analyst at SolarPower Europe.

The EU added more than 18 GW of new solar capacity in 2020, but it will need to add about 45 GW per year throughout this decade to meet its ambitious solar power goals. Solar is the fastest growing renewable energy source globally.

To create a domestic supply chain that could meet that demand, the EU would have to produce three times more polysilicon, 20 times more wafers, 42 times more cells and six times more modules, according to the Wood Mackenzie analysis.

The EU solar manufacturing industry, backed by the Commission, wants to scale up its capacity to 20 GW at each step of the value chain by 2025, an initiative estimated to require more than €8 billion in investments.