Lofty climate-change goals risk becoming empty promises

Harder Line

An overlapping mix of corporate pledges, investment fervor and government targets risk setting us up for a dangerous phase in the quest to tackle climate change: a lot more bark than bite when it comes to reducing greenhouse gas emissions.

At a high level, progress has been incredible.

More and more countries and corporations are pledging to reduce their emissions, compared to a baseline of essentially zero when the Paris Climate Agreement was signed in 2015.

Out of 198 countries, 136 now have net-zero targets, according to Net Zero Tracker, a coalition of four organizations.

Of the world’s largest publicly traded 2,000 companies, 683 have net-zero targets.

Meanwhile, investment in climate technologies is reaching record highs.

More than $35 billion went into venture capital deals last year, according to PitchBook. In addition, PwC recently calculated $222 billion in climate tech investments across VC and private equity between 2013 and the first half of last year.

But substantive progress is elusive when you look more closely.

Out of 15 technologies PwC examined, just a quarter of climate tech investments between 2013 and the first half of 2021 went to the five technologies representing 80% of emissions reduction potential, according to PwC’s State of Climate Tech 2021.

Those five are green hydrogen, food waste, cleaner foods/proteins, solar and wind.

Solar and wind are growing rapidly, but considering their potential impact, they’re “still significantly underfunded,” said co-author Emma Cox. “More investors need to take bets on proving out technologies with higher emissions reduction potential.”

Most (two-thirds) of the $222 billion is going toward transport, which accounts for just 16% of the world’s greenhouse gas emissions.

You see this pattern where you get the success story of Tesla, and it blazes the trail. There’s a stampede of unicorns – Lucid Motors, Rivian. It becomes easier and easier as you go down

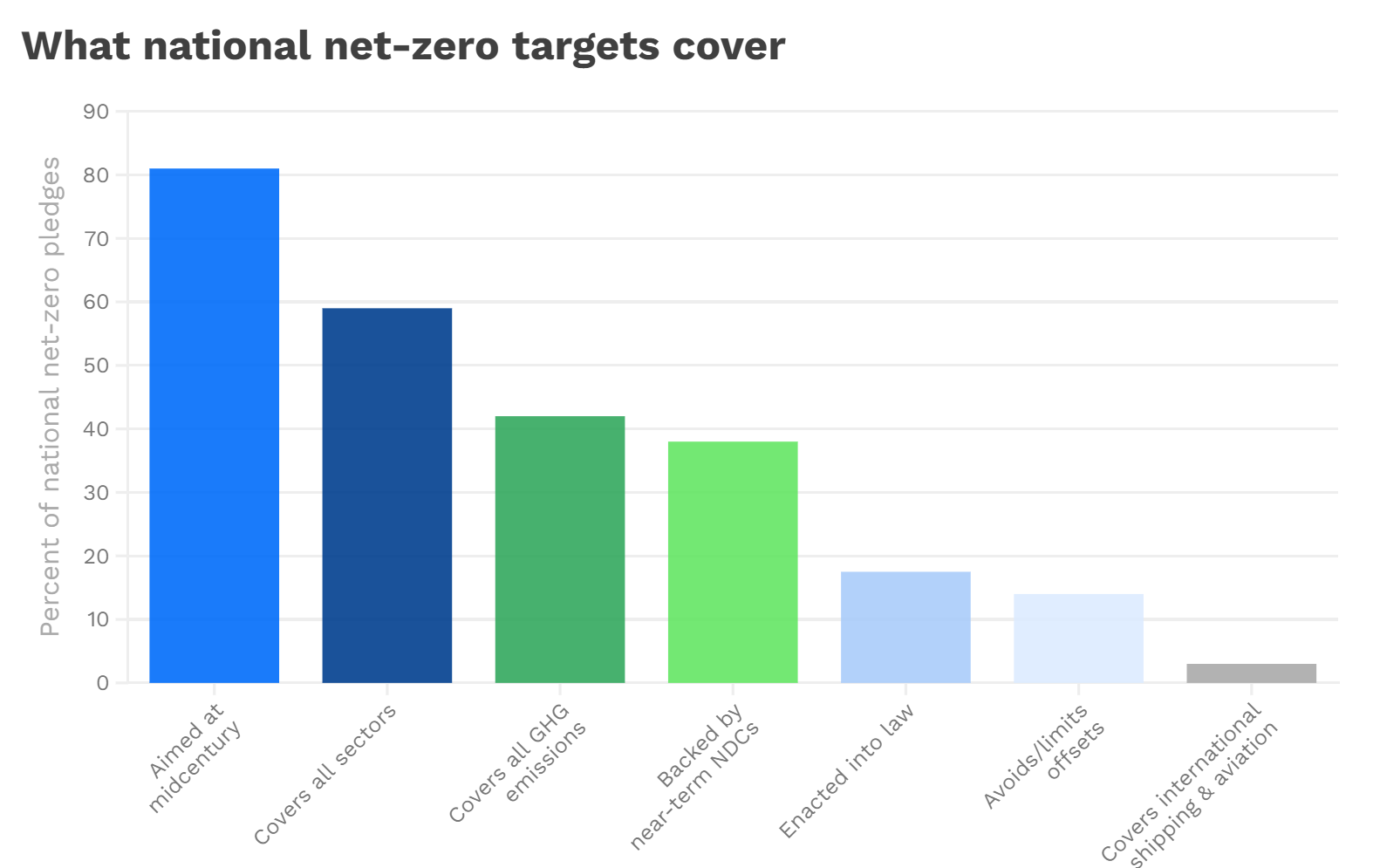

At the government level, most countries’ net-zero goals are much less robust than their rhetoric suggests.

According to a recent HSBC report, less than 60% of 74 national net-zero targets cover all sectors of the economy, and less than half cover all greenhouse gas emissions. That’s like a diet you only follow half the time.

What’s more, not even 20% have enacted their targets into law, according to Climate Watch, an online platform managed by World Resources Institute whose data is cited in the HSBC report.

Source: HSBC, World Resources Institute, Climate Watch • This analysis includes 74 net-zero national targets as of Nov. 18, 2021. NDC stands for National Determined Contribution, which are each country’s goals submitted in the Paris Climate Agreement.

The United States is among the 83% of countries without net-zero laws backing up such pledges. Although the recently passed infrastructure law puts more than $100 billion in climate and clean energy programs, Congress still hasn’t passed a more comprehensive bill that would get the U.S. a lot closer to its goal.

Only 14% of national net-zero pledges avoid or limit the usage of carbon offsets, which are increasingly controversial. Offsets are mechanisms that allow entities to make investments in one place, like planting trees or installing wind farms that counteract emissions elsewhere.

While companies dominate the offset market, 86% of countries also use offsets to some significant degree, according to HSBC. That means both corporations and governments are relying on them a lot.

Governments don’t regulate the use of carbon offsets, and different entities manage them unevenly, so verifying emission reductions is tough.

“The scaled-up use of carbon offsets will have to be accompanied by a radical enhancement of their quality and scaled-up regulatory scrutiny,” according to a recent peer-reviewed report in Nature Climate Change.

Take the case of Delta. Since 2015, the airline has purchased and retired more than 10 million voluntary carbon offsets from the Verified Carbon Standard, the largest voluntary carbon offset registry globally, according to Kyle Harrison, head of sustainability research at BloombergNEF, which just issued a report on offsets.

Some 1.7 million, or 17%, of these offsets were from natural gas plants in China, Harrison wrote for a recent article posted on the Bloomberg terminal that he shared with Cipher.

“These projects are likely able to monetize carbon offsets on the premise that they were built in place of a heavier-emitting coal project, but nonetheless can be misleading for customers,” Harrison wrote.

Chinese gas plants make up just 4% of the 39 million offsets Delta has retired since 2015, the company said in a statement to Cipher. It also said it’s increasing its investments in offsets that fully avoid emissions.

Although the price Delta paid for the offsets isn’t public, it’s likely vastly less than the hundreds of dollars per ton of CO2 some companies are paying to remove carbon from ambient air using technology, Harrison says.

Tech firms like Stripe, Microsoft and Square have purchased carbon removal services from Climeworks, a Switzerland-based startup whose huge, air conditioning-like machines suck CO2 from the sky.

Climeworks doesn’t disclose the prices it negotiates with clients, but a spokesperson says that the price per ton of carbon at its small-scale plant is between $650 and $900.

As the carbon offset market evolves and hopefully becomes more standardized, Harrison says the price of offsets should gradually get higher. That, in turn, should incentivize companies to invest primarily in the actual technologies we need to reduce emissions and remove carbon from the atmosphere.