Japan, an economic leader in Asia, lags on renewable energy

Latest News

TOKYO — Japan, the only Asian member of the elite Group of Seven countries (G7), is lagging in its efforts to decarbonize the world’s third-largest economy, according to climate advocates and scientists.

Despite recently releasing a new plan for achieving net-zero emissions by 2050, the country’s aim to continue deploying coal- and gas-fired power generation for decades to come could undermine a push by wealthy countries at the major climate summit known as COP28 to eliminate the use of this dirtiest of fossil fuels by the end of the decade.

Japan’s actions are also likely to complicate the European Union’s efforts to forge a deal aimed at phasing out all fossil fuels.

“Japan’s climate leadership really matters in the region. It’s still an economic powerhouse and politically has very strong influence,” said Uni Lee, an analyst with Ember, a global energy think tank.

This year, Japan has assumed the rotating presidency of the G7 — a collection of countries that brings together, along with Japan, the United States, the United Kingdom, France, Germany, Italy and Canada. Japan recently hosted a summit of national leaders that reaffirmed an “unwavering commitment” to the 2015 Paris Climate Agreement goals of holding global temperature rise to 1.5 degrees Celsius, which essentially means driving emissions down to net zero by 2050.

But climate and renewable energy advocates, including in Japan, worry the country’s plan for transitioning its energy system and economy gives short shrift to renewable energy and puts too much emphasis on prolonging coal- and gas-fired electricity generation plants.

Japanese officials say they will reduce greenhouse gas emissions by mixing these fuels with carbon-free ammonia produced by a nascent renewable-energy hydrogen industry. Japan may then export this “co-firing” approach to developing nations in Asia that also have large fleets of coal-fired power plants built to operate decades into the future, according to industry officials.

“I think the most important thing for the government is to try to keep thermal power plants and a fossil fuel-based energy system,” said Teruyuki Ohno, executive director of the Renewable Energy Institute, a renewable energy advocacy group based in Tokyo. “They’re trying to prolong the life of these plants.”

In its new energy system transition framework released in February, the Japanese government laid out plans to combust ammonia derived from hydrogen produced with either renewable energy or fossil fuels with their carbon emissions captured and stored.

The bulk of that ammonia would be imported from Australia, the Middle East and other countries able to make it inexpensively. Japan currently imports fossil fuels for 90% of its primary energy.

IHI Corp., a Japanese heavy industry manufacturer working on ways to construct and retrofit coal and gas turbines to burn ammonia, plans to demonstrate equipment next year capable of co-firing 20% ammonia with coal by next year and then 50% by 2028. Eventually, though, the company believes most thermal power plants in Japan will begin to migrate to new and retrofitted natural gas turbines that can burn 100% ammonia starting in 2027.

“We think for now the practical solution is co-firing, but it’s not our final goal. It’s just a first step to reduce carbon dioxide emissions quickly and economically,” said Yuji Nose, deputy general manager for public private partnership promotion in the company.

The government’s updated decarbonization strategy does not raise the overall targets for renewable energy, like solar and wind, from its previous goal of 36-38% of the country’s total energy mix by the end of the decade, despite dramatic cost declines in renewable technologies and projections that using ammonia co-firing will be expensive.

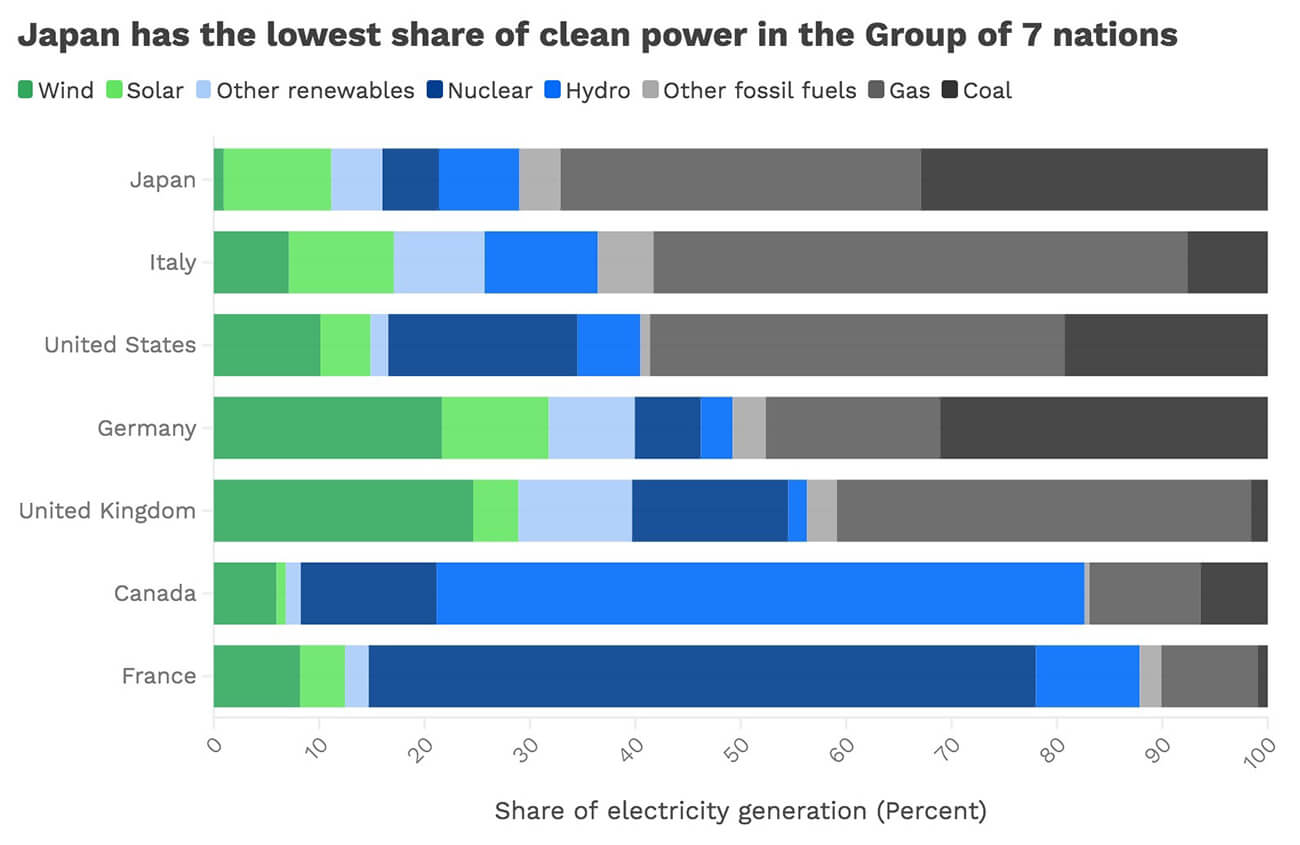

Renewable energy made up 19% of Japan’s electrical power generation in 2019; when including nuclear power, Japan’s clean energy mix rises to about 24%.

Renewable energy advocates argue much higher levels of renewable energy are achievable in Japan, which has seen a boom of solar installations over the last decade and has some of the world’s best potential for wind power, especially offshore.

The Renewable Energy Institute recently urged the government to adopt a target of 80% renewable energy by 2035, including reaching at least 45% by 2030, according to Ohno.

An ambitious renewable energy push could transition Japan’s electrical power generation to 90% non-fossil fuel energy by 2035 at costs lower than today’s fossil fuel-based system, according to a study published last year by the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, part of the U.S. Energy Department.

Renewable energy advocates point to Japan’s goals for wind power as falling particularly short of the country’s potential. Japan has about 18,500 miles of coastline, enough to stretch three-quarters of the way around the globe and the sixth longest of any country. Much of that coast is windy most of the year.

Japan has the highest share of coal generation for electrical power (33%) in the G7 along with the lowest share of wind power — 1% compared to 11% on average for G7 countries, according to a recent Ember report. In an April communique, climate, energy and environmental ministers from the G7 targeted 150 gigawatts (GW) of new offshore wind by 2030, but Japan aims to have only 5.7 GW up and running by then, just 4% of the G7 goal.

Source: Ember • “Other renewables” includes bioenergy, geothermal, tidal and wave generation. “Other fossil fuels” includes generation from oil and petroleum products, as well as manufactured gases and waste.

Japan’s nuclear industry, which once generated nearly a third of the country’s electricity, shut down almost completely after a 2011 disaster when an earthquake-induced tsunami overwhelmed a facility in the city of Fukushima. Late last year, the government changed course and said it plans to re-start some idle nuclear reactors.

Despite its slow start, Japan will continue growing renewable energy, mainly because it’s likely to be less expensive overall than extending the life of coal plants by burning expensive ammonia alongside fossil fuels, said Yamato Kawamata, a senior research analyst with the energy consultancy Wood Mackenzie in Tokyo.

Wood Mackenzie calculated that even a 20% ammonia and coal mixture — a relatively low level compared to the 50% or someday even 100% ammonia levels Japanese officials are targeting — would cost more than utility-scale renewable energy, he said.

Still, deploying “carbon free” ammonia to avoid the upfront investment to build out new renewables and avoid the cost of abandoning generation plants with many years of payment obligations ahead could be an attractive option for Japanese utilities, Kawamata said.

Relying even more heavily on offshore wind energy than current plans would also require even bigger outlays for new transmission cables from sea to land and from sparsely populated regions where Japan’s wind potential is greatest to the cities. Wind projects have also met with local opposition, leading some to be abandoned.

Those actions could be a difficult financial burden for the government at a time when its economy has been struggling for decades, the population is declining and the government is vowing to double its military budget.

As Asia’s only country in the G7, Japan’s continued embrace of coal and natural gas could dilute calls from some of its peers to phase out fossil fuels at COP28 later this year, and beyond.

“Japan’s climate leadership is going to matter,” said Ember’s Lee. “It really does have a big influence on countries’ ambitions, and actual deployment.”

IHI Corp. plans to demonstrate equipment capable of co-firing 20% ammonia with coal in thermal electrical generation plants next year. The company has not determined when it may begin selling the equipment, a spokesman said. An earlier version of this story said the company plans to sell the equipment next year.