Why we can’t sacrifice our way out of climate change

Harder Line

Matt Rogers helped teach millions of homeowners to look for the leaf symbol on their Nest thermostats to save money—and curb climate change.

Rogers, co-creator of Nest, is now trying to replicate that success in the kitchen. You can have a cleaner kitchen, Rogers says, that also happens to reduce emissions.

His new company, Mill, encourages people to redirect their food waste from the trash—where it eventually ends up in landfills emitting heat-trapping methane gas—to a new kind of electronic bin that dehydrates food and turns it into a coffee grounds-like material suitable for chicken feed.

“It’s a better kitchen experience,” Rogers said in a recent interview. “No smell, no fruit flies, no icky bags. It’s been really nice. Our bin is a bottomless pit.”

That perspective goes counter to a constant drumbeat of headlines urging us to sacrifice our way of life in Western democracies—and especially the United States—to tackle climate change.

We should eat less meat. We should fly less. We should drive electric cars—and definitely not the SUVs Americans love.

The moral argument is clear and compelling: Historically, the U.S. is the world’s largest emitter of greenhouse gases, and we owe it to our fellow Earth inhabitants to curb our carbon-heavy lifestyles first and most.

Morality isn’t an effective argument, however, judging by most people’s response to the Covid-19 pandemic as it enters its fourth year.

Even when the pandemic threat was most acute, the concept of wearing a mask for a few months to protect people’s own health and the health of those around them tore countries—especially the U.S.—apart.

With climate change, we’d have to ask people to sacrifice the way they live for the rest of their lives to address a problem that is not going to be solved in our lifetimes.

The energy crisis engulfing Europe after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine is also showing the limits of even relatively significant individual sacrifices during an extreme wartime scenario.

Responding to both high prices and government pleas to reduce usage, consumer behavior in the European Union may have saved between three and 10 billion cubic meters of natural gas last year, according to the International Energy Agency. At the high end of that range, the amount saved is still less than 3% of the bloc’s 2021 consumption.

The resistance to and limited effect of personal sacrifice are why I (sometimes begrudgingly) conclude we must look to capitalism and the innovation of new and better technologies to save us.

“A population as a whole doesn’t generally sacrifice its way to change,” said Anthony Leiserowitz, founder and director of Yale University’s Program on Climate Change Communication, and a senior research scientist at the Yale School of the Environment.

Consumer choices, influenced by government policy, product availability and costs, are integral to combating climate change.

The IEA estimates that around 55% of the cumulative emissions reductions in its scenario of achieving net-zero emissions by 2050 are linked to consumer choices, including purchasing electric cars or installing heat pumps.

Leiserowitz calls a small but influential segment of any population “early adopters.”

“These people can be motivated by something one person might call sacrifice, but they might call living out their values,” Leiserowitz said. “Early adopters are absolutely critical because they provide social proof that an innovation works and is desirable.”

This process is how we went from the Nissan Leaf targeting a small subset of “early adopters” with polar bear commercials in 2011 to the Ford F-150 Lightning promoting its towing capacity (among other non-climate features) in 2019.

In the vast gulf between the Leaf and electric F-150 consumers, Tesla proliferated.

“You don’t switch to make the world better, you switch because it’s a better car,” said Matt Eggers, a former vice president of North American sales at Tesla. “We focused on safety and the fact you don’t have to go to the gas station, and we didn’t talk about environmental benefits until the customer asked about it the second time.”

Eggers is now an investor at Breakthrough Energy Ventures, which is among the investors of Mill, along with other big-name venture capital firms like Prelude Ventures and Energy Impact Partners.

Mill will also likely be relying on so-called “early adopters” as its first customers.

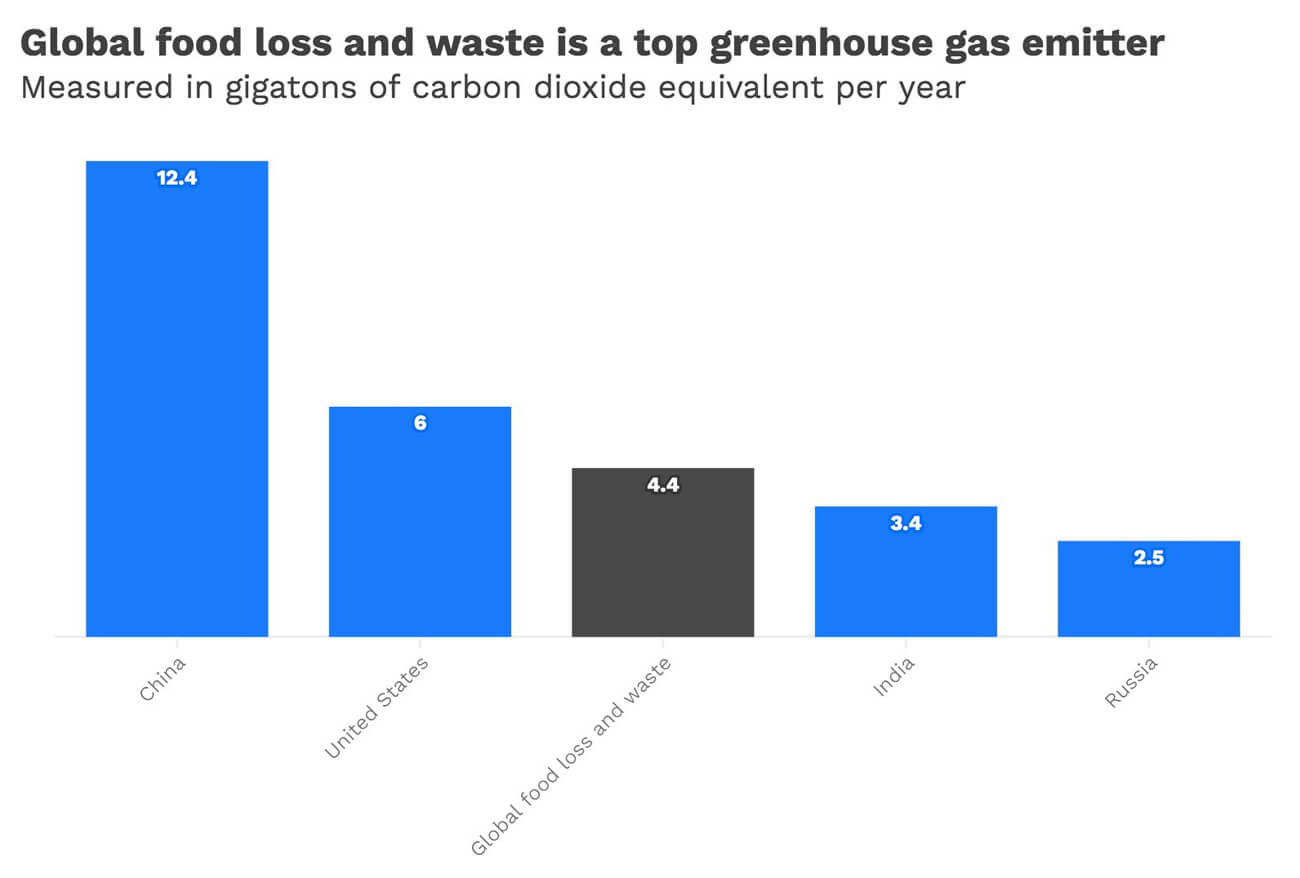

Right now, food takes up more space in landfills than anything else and more than half of that waste comes from kitchens, Rogers wrote on LinkedIn when announcing Mill last week.

Households can avoid a half-ton of greenhouse gas emissions a year by signing up with Mill, according to a preliminary study the company conducted. That’s the same as driving the distance between Miami and New York City in a typical gasoline-powered car, a Mill spokesperson said.

Rogers is sitting at the juncture between human behavior and systemic change.

“We are more likely to act pro-environmentally if the systems allow us to do so,” said Linda Steg, a professor of environmental psychology at the Netherlands’ University of Groningen. “Currently, the systems include all kinds of incentives going in the wrong direction.”

Flying can be cheaper than public transit and oil, natural gas and coal still receive far more government subsidies than clean energy, Steg points out.

“Systemic changes are needed, but at the same time, we as individuals can increase the likelihood of these systemic changes happening by demonstrating with our behavior and voting,” Steg said.

Right now, it’s cheaper and easier to throw food in the garbage than anything else (just 4% of U.S. food waste is composted).

“A lesson we learned at Nest is that by making people aware of how much they’re wasting, we see that people tend to change their behavior over time,” Rogers said.

Unlike a thermostat, which has a one-time cost, a Mill bin costs $33 a month for a yearly subscription (more if you go monthly).

Such recurring costs could turn off customers, many of whom said in a survey by Mill they’re okay with tossing food in the garbage, according to a Bloomberg article last week going into more detail about the company.

Indeed, Mill isn’t a perfect solution to our waste problems, just like Tesla isn’t the ideal answer to our gasoline-powered car problems and Nest hasn’t solved all our woes stemming from fossil fuel electricity.

But each offers something that improves our lives while helping the planet.

As for me, I’m considering signing up for Mill. Con: We don’t have a lot of extra space in our kitchen for another plugged-in device. Pro: Just the other day, my compost bag spilled all over the ground and it was a messy pain to clean up.

Editor’s note: Breakthrough Energy Ventures (BEV) is a venture capital fund within the Breakthrough Energy network, which also supports Cipher.